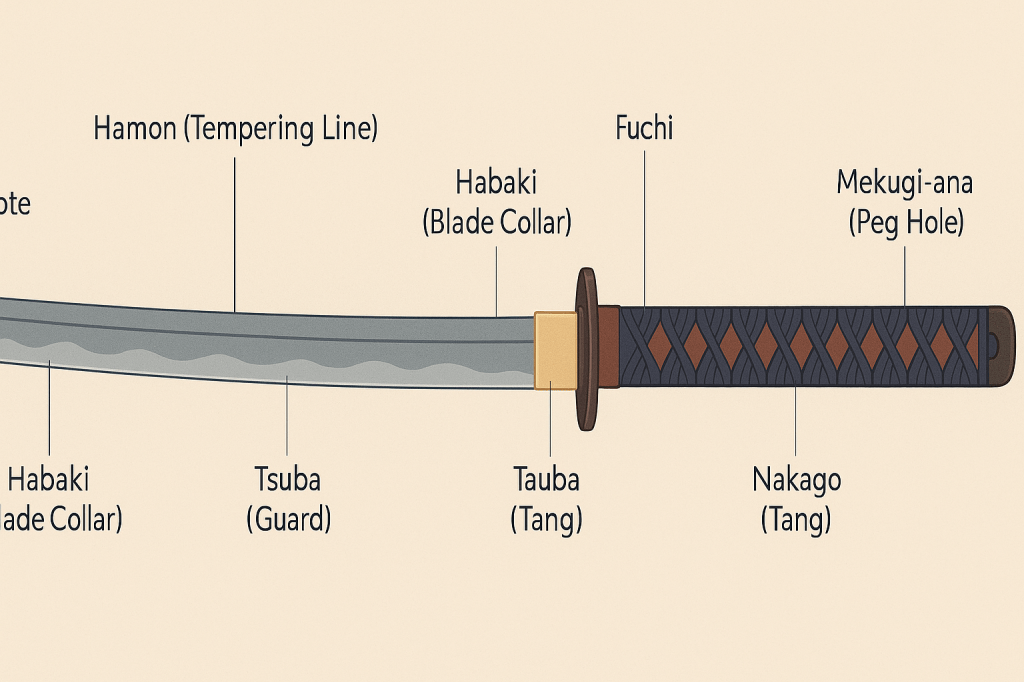

The Japanese sword has different parts, each of those having a unique name. This post is about a quick reference to these parts.

Reading time (estimated):

11–17 minutes

The parts of the Japanese sword can be organized in two groups: the parts of the sword (parts A to D) and parts of the saya (scabbard). Here is the list according to the above.

Parts of the sword

- Tsuka (柄): the handle of the Japanese sword. Structurally, any sword can be broken down into two fundamental components: the blade and its handle. And the tsuka is precisely that. It functions as a protective and ergonomic covering for the lower, unsharpened part of the blade, known as the nakago (the tang). In essence, the tsuka encapsulates the tang, allowing the sword to be wielded, gripped, and controlled. Conceptually, this is not far from how the handle of a kitchen or utility knife covers the tang of the blade. However, in the case of a katana or similar traditional sword, the tsuka is far more than a grip. It is a carefully engineered and multilayered structure, integrating components like same, tsuka-ito, menuki, and kashira, all of which contribute to its balance, functionality, durability, and even symbolic meaning. A properly constructed tsuka is essential not only for combat performance but also for the integrity of the entire sword assembly.

- Kashira/Tsuka-Gashira (頭 / 柄頭): this is the cap at the end of the handle (tsuka). Quite often, it serves not just a functional role but a decorative one as well, typically chosen to match the aesthetic preferences of the sword-smith or the person who commissioned the blade. Its design can range from minimal to highly ornate, sometimes depicting mythological or seasonal motifs.

- Kashira-Game (頭金): the term used to denote the actual metal fitting at the end of the handle. It is functionally equivalent to “kashira” but with a subtle distinction. Kashira emphasizes the position, as in “the head” (of the sword) or “bottom of the tsuka”, while kashira-gane places emphasis on the material, literally meaning “metal at the head.” In many discussions, especially outside Japan, these terms are used interchangeably, but knowing the nuance adds clarity.

- Same/Same-hada (鮫 / 鮫肌): these terms also describe essentially the same component but from two different perspectives. Same (pronounced “sah-meh”) refers to the actual ray or shark skin used to wrap the tsuka, prized for its rough surface and grip-enhancing properties. Same-hada refers specifically to the texture, literally the “ray-skin grain.” On close inspection, the surface reveals a nodular or “pimpled” pattern. The size and symmetry of these nodes reflect the quality of the skin: larger nodules, especially a prominent central one, are rarer and therefore more prestigious.

- Makidome (巻留): these are the small, finishing knots made at the end of the tsuka-ito (handle wrap). Functionally, they secure the wrap in place, but aesthetically, they also act as subtle punctuation marks in the tsuka‘s visual rhythm. There are various styles of makidome, and a skilled tsukamaki craftsman will often adjust them to suit the sword’s overall character.

- Tsuka-Ito/Tsukamaki (柄糸 / 柄巻き): tsuka-ito refers to the braided cord or thread used to wrap the handle, traditionally made from silk, cotton, or leather. It is laid over the same and secured in a crisscross diamond pattern. Tsukamaki is the wrapping technique itself, i.e. the art and method of applying the ito. Beyond aesthetics, proper tsukamaki provides grip, shock absorption, and even slight directional feedback during cuts.

- Mekugi Nakago (目釘 茎): mekugi is a small peg, typically made of bamboo, that secures the blade into the handle. It passes through a hole in the tang of the blade, known as the nakago. The nakago is the tang, or unsharpened portion of the blade that fits into the tsuka. Traditional swords usually have a single mekugi, but some styles or schools may opt for two. A well-fitted nakago and properly aligned mekugi ensure the blade stays firmly attached to the handle without the need for adhesives or mechanical fasteners.

- Tsuba area (mentioned as “Handle” in the image): this is the hand-guard zone of the sword: it includes the tsuba itself, typically a round or occasionally angular guard positioned between blade and handle, and the immediate collar and spacer fittings (fuchi and seppa). Its core purpose is to shield the wielder’s hand from sliding onto the cutting edge during thrusts or when blades clash, while also contributing to overall balance and, in many periods, acting as an artistic statement of status.

- Fuchi (縁): the hilt collar immediately above the tsuba. Crafted from iron, brass, or copper, it reinforces the top of the tsuka, working with the kashira to ensure structural integrity. Its purpose and pairing with kashira are documented in glossaries and anatomical descriptions.

- Tsuba (鍔): this is the hand guard of the sword. Typically made of iron (sometimes copper, brass, or shakudō), its primary function is to protect the wielder’s hand when blades meet in combat. It prevents the opponent’s sword from sliding toward the hands. As indicated in multiple sources, tsuba also contribute to balance and became ornate art objects during the Edo period.

- Seppa (切羽): thin spacer washers positioned above and below the tsuba. They hold the assembly tightly together, preventing lateral movement and maintaining alignment. The term “seppa” literally means “cut feather,” and their function is well-documented.

- Habaki (鎺): a wedge-shaped collar located at the base of the blade, just above the tsuba. It secures the tsuba, locks the sword into the saya, and creates friction necessary for a controlled draw. It plays a crucial role in both function and ritual.

- Sori (反り): refers to the curvature of the blade, a defining characteristic of the katana. Variants include torii-sori, koshi-sori, etc. Without proper sori, a blade cannot be classified as a katana.

- Mune (棟): the spine (back) of the blade, the unsharpened ridge opposite the cutting edge. Typically constructed of softer steel, it provides flexibility and structural strength.

- Hamon (刃文): the temper line visible along the blade edge, created by differential clay quenching. It distinguishes the hardened yakiba (hardened cutting zone) from the softer ji and is both functional and artistic.

- Yakiba (焼刃): refers to the hardened cutting zone of a Japanese sword blade, specifically the portion of the edge that has undergone differential heat treatment (yaki-ire), making it harder than the rest of the blade.

- Hi/Bo-hi (樋 / 棒樋): these are grooves carved into the blade to reduce weight and adjust balance without compromising structural integrity, functionally similar to I-beam construction. They also affect the blade’s resonance, producing an audible tachi-kaze (“cutting wind”) when swung correctly, which is valued in martial arts practice. Often mislabeled as “blood grooves,” this is a modern myth. There is no historical or technical evidence that bo-hi was intended to assist with blood drainage or blade withdrawal after stabbing.

- Nagasa (長さ): The effective blade length, measured from the munemachi (the notch at the base of the blade, just under the tsuba) to the kissaki (tip of the blade). This measurement excludes the tang (nakago) and represents the actual cutting length of the blade. Typical katana have a nagasa of around 80 cm (31 in), which is approximately 2 shaku 6 sun in traditional Japanese units (1 shaku = ~30.3 cm; 1 sun = ~3.03 cm). This length was historically tailored to the swordsman’s height, fighting style, or era-specific conventions.

- Shinogi (鎬): The ridge line separating the angled edge face from the flat midsection (shinogi-ji). It defines the blade’s geometry and contributes to its structural integrity. The height and position of the shinogi affect cutting performance and stiffness. A higher shinogi yields a sharper edge, while a lower one increases durability and resistance to bending.

- Shinogi-Ji (鎬地): The flat surface between the shinogi ridge and the spine (mune) of the blade. Often polished more brightly, it highlights the blade’s geometry and the position of the shinogi. The shinogi-ji contributes to the blade’s rigidity, balance, and structural definition, playing a subtle but important role in both performance and aesthetics.

- Ji/Hiraji (地 / 平地): The flat surface area of the blade located between the cutting edge (ha) and the ridge (shinogi). This region may be plain or feature visible grain patterns known as jihada, which reflect the steel’s forging and folding. The term ji refers broadly to the entire body of the blade excluding the edge (hamon) and spine (mune), while hiraji specifically denotes the flat, polishable section between the shinogi and the hamon. Both are important to the blade’s aesthetic character, structure, and polish quality.

- Yokote (横手): the defining line that separates the main body of the blade from the tip (kissaki). It marks the point where the cutting plane of the blade transitions into the specialized geometry of the tip. The yokote is typically a straight, sharply polished line and is essential for defining the shape, proportion, and strength of the kissaki. Its presence is characteristic of traditional shinogi-zukuri blades and contributes to both visual clarity and functional precision in the sword’s design.

- Shinogi-zukuri (鎬造り): the most common and recognizable blade geometry in traditional Japanese swords, especially katanas and wakizashi. It is defined by a prominent ridge line (shinogi) that runs along both sides of the blade, separating the flat surface (shinogi-ji) from the angled edge section (hira-ji).

- Mono-Uchi (物打ち): The primary cutting zone of the blade, typically located in the upper third, just above the yokote. This section is where slashing strikes are most effective, due to the optimized leverage and blade velocity at this range. In classical swordsmanship, the mono-uchi is considered the sweet spot for delivering precision and power, especially in techniques emphasizing fluid, single-cut engagement. Its exact placement and length can vary slightly depending on the blade’s nagasa and intended use

- Ha (刃): The cutting edge of the blade, honed to a razor-sharp finish. It is the most critical and lethal part of the sword, formed by differential heat treatment (yaki-ire) that gives it extreme hardness for edge retention while the rest of the blade remains more flexible. The ha runs the full length from the base to the kissaki, and its profile (including curvature and thickness) directly influences the sword’s cutting dynamics, durability, and ease of sharpening.

- Hasaki (刃先): Refers to the physical line of the edge, especially the beveled thickness at the start of the kissaki. The term literally means “edge tip” and is crucial in determining how the point of the blade performs during piercing or thrusting. A well-crafted hasaki ensures the tip remains sharp and structurally sound, balancing penetration ability with resistance to chipping or deformation under stress.

- Boshi (帽子): The continuation of the hamon (temper line) into the kissaki area. It curves around the tip and terminates near or at the yokote, forming a distinct pattern that reveals the smith’s control during heat treatment. The shape of the boshi, whether straight, sweeping, turning back, or disappearing, is one of the key features evaluated in sword appraisal and authentication. Inadequate or irregular boshi may indicate poor craftsmanship or improper quenching.

- Kissaki (切先): The tip of the blade, beginning at the yokote and extending to the point. Its geometry (i.e. length, curvature, and angle) greatly affects thrusting performance, tip control, and visual balance. Common kissaki types include chū-kissaki (medium), ō-kissaki (large), and ko-kissaki (small). A well-defined kissaki is not just functional, but also a hallmark of refined sword design and polish.

Parts of the saya (scabbard)

- Saya (鞘): the scabbard or sheath of the sword, traditionally made of lightweight wood (often ho or magnolia) and lacquered for durability and aesthetics. The saya protects the blade from moisture and damage, ensures safety during transport, and contributes to the sword’s overall balance. A properly fitted saya ensures smooth draw and re-sheathing (nōtō) without undue friction or risk of edge contact.

- Koiguchi(鯉口): the mouth of the saya, where the blade is inserted. Typically reinforced with horn or metal to prevent splitting, it must fit the habaki precisely to ensure blade retention and secure seating. The term literally means “carp’s mouth,” referencing the oval shape and traditional symbolism of perseverance and strength.

- Kurigata(栗形): a knob-like fitting on the side of the saya, traditionally made of buffalo horn or metal, through which the sageo (cord) is threaded. Its shape resembles a chestnut (kuri), and it serves as the attachment point for securing the sword to the wearer’s obi (belt) or armor via the sageo.

- Shito-Dome(鵐目 or 鵐止): small metal fittings or eyelets inserted into the kurigata’s holes to protect the cord from wear and add decorative detail. Their name means “plover’s eye,” a poetic reference to the small, circular form. Shitodome are often crafted from copper, brass, or shakudō, and are considered a sign of refinement in koshirae (mounting).

- Sageo(下緒): the cord threaded through the kurigata and tied around the saya. Made of silk, cotton, or leather, the sageo is used to secure the sword to the obi, and in some schools, also features in ceremonial tying techniques or combative retention methods. Its style, color, and knot often reflect the sword’s owner, school, or occasion.

- Kojiri(鐺): the end cap or chape of the saya, reinforcing the tip and protecting it from impact or wear. Typically made of horn or metal, it also completes the visual harmony of the scabbard. In some styles, the kojiri is flush with the wood; in others, it is a prominent, shaped fitting.

Extra info

- Koshirae (拵): the mounting ensemble of a Japanese sword, referring to all external fittings and components used when the blade is worn or displayed in its complete, functional form. This includes the tsuka (handle), tsuba (guard), fuchi-kashira (collar and pommel), menuki (ornaments), sageo (cord), and saya (scabbard), among others. Koshirae contrasts with the shirasaya (plain wooden storage mount) and serves both practical and aesthetic purposes. In historical contexts, the koshirae reflected the owner’s social rank, school, battlefield readiness, and artistic sensibility. Its quality and harmony were considered as important as the blade itself in many periods of Japanese sword culture.

- Shirasaya (白鞘): literally meaning “white scabbard,” the shirasaya is a plain, undecorated wooden mounting used for the storage and preservation of a Japanese blade. It consists of a minimalist tsuka (handle) and saya (scabbard), typically made from ho wood (Japanese magnolia), which is stable and non-reactive—ideal for protecting the blade from moisture and corrosion. Unlike the koshirae, the shirasaya is not intended for combat or wearing. It lacks fittings such as tsuba, sageo, or fuchi-kashira. Some shirasaya feature calligraphic inscriptions (sayagaki) documenting the sword’s lineage, smith, and appraisal. Its clean aesthetic serves both practical and curatorial roles, especially in collections and museums.

References

- L. Kapp, H. Kapp, and Y. Yoshihara, The Craft of the Japanese Sword. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International, 1987.

- K. Nagayama, The Connoisseur’s Book of Japanese Swords. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International, 1997.

- T. Tsuchiko and K. Mishina, The New Generation of Japanese Swordsmiths. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International, 2002.

- S. Turnbull, Katana: The Samurai Sword. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2010.

- “Katana,” Wikipedia, [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Katana. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- “Japanese sword mountings,” Wikipedia, [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_sword_mountings. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- “Tsuba,” Wikipedia, [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsuba. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- The British Museum, “Japanese sword mountings (katana koshirae),” Collection Online, [Online]. Available: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- Tokyo National Museum, “Japanese sword glossary,” [Online]. Available: https://www.tnm.jp/modules/r_collection/index.php. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- JapaneseSwordIndex.com, “Japanese Sword Glossary,” [Online]. Available: https://japaneseswordindex.com/glossry.htm. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- Swordis.com, “33 Essential Katana Parts Everyone Should Know,” [Online]. Available: https://swordis.com/blog/katana-sword-parts. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- Reliks.com, “The Habaki – Parts of a Japanese Katana,” [Online]. Available: https://www.reliks.com/functional-swords/japanese-swords/habaki/. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- Samurai Museum Shop, “Tsuba – Japanese Sword Guard,” [Online]. Available: https://www.samuraimuseum.jp/shop/product-category/decorations/tsuba. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- Tozando Co., Ltd., “Japanese Sword Fittings and Koshirae,” [Online]. Available: https://www.tozandoshop.com. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- Romance of Men, “Katana Tsuba: A Definitive Guide to Understand This Sword Part,” [Online]. Available: https://romanceofmen.com/blogs/katana-info/katana-tsuba-definite-guide-to-understand-this-sword-part. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

- Es.wikipedia.org, “Hasaki,” Wikipedia en Español, [Online]. Available: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasaki. [Accessed: 16-Jun-2025].

Leave a comment