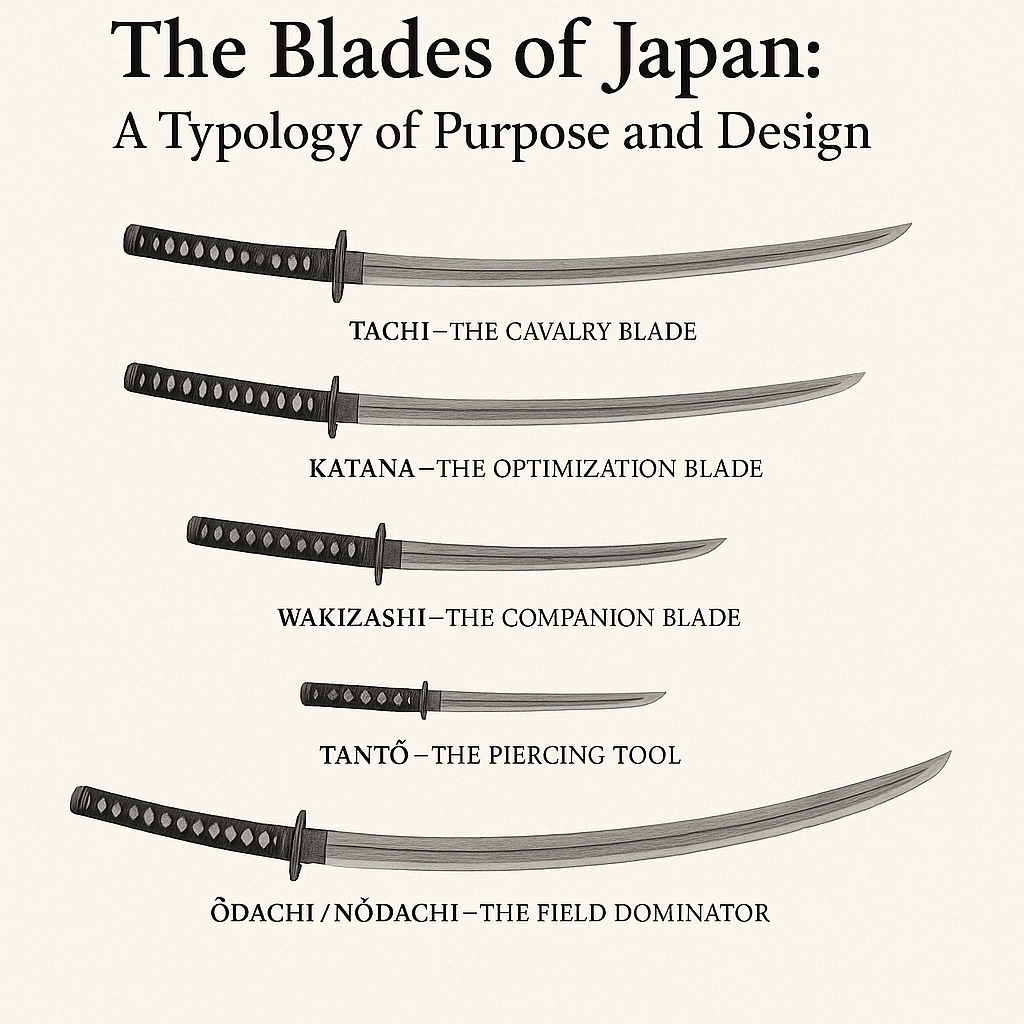

A condensed view on how tachi, katana, wakizashi, and other iconic blades evolved through design, physics, and battlefield needs. A small dive into Japanese sword types from a STEM perspective.

Reading time (estimated):

Japanese swords are more than weapons, they are dynamic expressions of function and form, crystallized through centuries of battlefield innovation and cultural refinement. Viewed through a STEM lens, these blades reveal an interplay between physics, biomechanics, and strategic adaptation. This post reframes their typology not as a static list, but as an evolving system of engineered tools embedded in martial culture. The types of swords mentioned have their name and the historical periods where they were mainly used. Here we go!

Chokutō (直刀): Kofun (300 to 538 CE) to early Heian (794 to 1185 CE)

The chokutō, a straight, single-edged blade, reflects early Chinese influence before the discovery of the advantages of curvature. Primarily used in ceremonial and early military roles, it lacked the dynamic slicing properties of later curved swords. Its design relies more on linear thrusting and chopping actions, which limited its biomechanical efficiency in rotationally-based combat systems.

Tachi (太刀): Heian (794 to 1185 CE) to Muromachi (1336 to 1573 CE)

The tachi emerged during the Heian period as a dominant cavalry weapon. It was worn edge-down and featured a deeply curved blade, which made it particularly effective for delivering slashing attacks from horseback. The curvature allowed riders to convert vertical momentum and body mass into angular velocity, maximizing the slicing potential of each strike. In physical terms, the tachi exemplifies the application of gravitational torque through a moving lever arm, essentially turning the samurai’s upper body into a kinetic engine.

Ōdachi (大太刀): Late Kamakura (1185 to 1333 CE) to Nanbokuchō (1336 to 1392 CE)

The ōdachi, or “great tachi,” is a massive sword often exceeding 100 centimeters (3 shaku and 3 sun) in blade length. Originating in the late Kamakura period and reaching ceremonial prominence during the Nanbokuchō and Muromachi periods, the ōdachi served both battlefield and symbolic functions. In warfare, its long blade offered substantial reach and cutting power, but it was often too large to be worn at the hip, requiring either hand-carrying or assistance from an attendant.

Beyond its use in combat, the ōdachi frequently appeared in shrine offerings, processions, and rites, reflecting its elevated status. Its mounting and polish retained the elegance of the tachi, and in many cases, forging such blades demonstrated a swordsmith’s technical prowess. From a mechanical standpoint, the ōdachi leveraged extreme blade length and distal mass to generate high rotational inertia, ideal for delivering devastating downward or diagonal cuts when space and stance permitted.

Nōdachi (野太刀): Muromachi (1336 to 1573 CE) to Sengoku (1467 to 1603 CE)

The nōdachi, or “field tachi,” emerged in the Muromachi period as a pragmatic battlefield weapon tailored for use by foot soldiers. While similar in size and shape to the ōdachi, the nōdachi lacked its ceremonial trappings and was optimized for practical use in open terrain. It was intended primarily for anti-cavalry tactics, enabling infantry to strike with reach and force before the enemy could close in.

Unlike the more refined ōdachi, the nōdachi was rugged, utilitarian, and frequently carried slung across the back for mobility. In combat, it demanded strength, coordination, and open space, unsuited for tight formations but highly effective in skirmishes and charges. The blade’s length amplified cutting power through torque, converting the wielder’s body motion into broad-arc slashes that could break through armor or disrupt charging formations.

Uchigatana (打刀): Muromachi (1336 to 1573 CE)

As battlefield environments grew more complex, the uchigatana emerged to meet new tactical needs. Unlike the tachi, it was worn edge-up and positioned for rapid deployment from the hip. It represents the intermediate evolutionary step between the tachi and katana, optimized for infantry use where reaction time and adaptability were paramount. Its introduction marked a democratization of sword use among lower-ranking samurai and foot soldiers.

Katana (刀): Muromachi (1336 to 1573 CE) to Edo (1603 to 1868 CE)

By the Kamakura period, shifting combat needs prompted the development of the katana. This blade retained curvature, though less pronounced than the tachi, and was worn edge-up to enable faster draw and strike. Its typical length of around 70 centimeters (2 shaku 3 sun) allowed for both reach and control. From an engineering standpoint, the katana represents a rebalanced compromise between inertia and maneuverability. Its slight curve enhances draw-cut efficiency, reducing friction across the target medium and optimizing shear stress distribution during motion.

Wakizashi (脇差): Muromachi (1336 to 1573 CE) to Edo (1603 to 1868 CE)

The wakizashi functioned as a secondary weapon often carried with the katana, forming the daishō (大小) pairing. Shorter in length, typically 30 to 60 centimeters (~1 to 2 shaku), it allowed for rapid deployment in confined spaces where a full-sized blade would be unwieldy. The wakizashi also played a central role in ritual suicide (seppuku), adding psychological and symbolic weight to its utility. In constrained environments such as narrow corridors or interior chambers, the wakizashi‘s shorter moment arm allowed efficient control and angular acceleration, an important consideration in interior close-quarters combat.

Tantō (短刀): Heian (794 to 1185 CE) to Edo (1603 to 1868 CE)

The tantō, a straight or slightly curved dagger between 15 and 30 centimeters (~0 shaku 5 sun to 1 shaku) in length, served as a weapon of last resort and a specialized armor-piercing tool. Its acute geometry allowed for concentrated force delivery over a minimal surface area, making it a textbook case of pressure-based penetration. In physics terms, the tantō‘s effectiveness arises from its ability to produce high-pressure force vectors due to its narrow tip and compact form factor.

Kodachi (小太刀): Kamakura (1185 to 1333 CE) to Muromachi (1336 to 1573 CE)

The kodachi, a short sword longer than a tantō but shorter than a tachi, found favor among younger warriors or those restricted by weapon-length laws. Its utility lies in its intermediate size, making it suitable for both open and enclosed combat scenarios. In some historical contexts, it allowed samurai to maintain martial presence without violating sumptuary restrictions on blade length, making it a strategic and legal compromise.

Nagamaki (長巻): Kamakura (1185 to 1333 CE) to early Muromachi (1336 to 1573 CE)

The nagamaki merges characteristics of a polearm and a sword. Its long handle, nearly equal in length to the blade, allowed for two-handed sweeping strikes with high torque and reach. Used effectively in open-field and anti-cavalry applications, the nagamaki’s grip enables large-radius attacks with improved leverage control. Its mechanical advantage is clear, it distributes force across a broader moment arm, reducing stress on the wrist while maintaining cutting velocity.

Shinobi-gatana (忍刀): Sengoku (1467 to 1603 CE)

Often associated with covert operations and the ninja tradition, the shinobi-gatana was typically shorter, straighter, and less ornate than samurai blades. It was optimized not for honor-bound duels but for utility, capable of prying, climbing, or silent incapacitation. Its simplicity reflected its role as a multi-tool in the service of asymmetrical warfare. In this sense, it was closer in concept to modern tactical gear than to aristocratic armaments.

Evolutionary Arc and Systemic Thinking

The development of Japanese swords maps directly onto changes in terrain, armor, tactics, and social organization. Long, sweeping blades gave way to more efficient, compact forms as battlefield engagements narrowed and personal combat became more prominent. Tactically, this reflects a shift from cavalry-based shock tactics to precision and rapid engagement, mirroring transformations seen in other technological systems where miniaturization and speed replace mass and scale.

From a systems perspective, Japanese swords cannot be fully understood in isolation. They co-evolved with armor types, martial arts systems (kenjutsu, iaijutsu), architectural environments, and even legal codes. Each blade is part of a distributed martial solution, designed not only to cut, but to function within the constraints and affordances of a complete ecosystem.

References

- K. Nagayama, The Connoisseur’s Book of Japanese Swords, Kodansha International, 1997.

- J. Yumoto, The Samurai Sword: A Handbook, Tuttle Publishing, 2012.

- W. M. Hawley, Japanese Swordsmiths, Hawley Publications, 1966.

- H. Sato, The Japanese Sword: A Comprehensive Guide, Kodansha, 1983.

- R. Ogawa, “The Structural Mechanics of the Japanese Sword,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology, vol. 140, no. 1–3, pp. 15–20, 2003.

- M. Kapp and H. Yoshihara, The Art of the Japanese Sword, Tuttle Publishing, 2015.

- T. Kanzan, “Functional Analysis of the Katana Blade Geometry,” in Proceedings of the Japan Society for Mechanical Engineers, vol. 110, pp. 75–82, 2009.

- G. Cameron Stone, A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor, Dover, 1999.

- Y. Tokuno, “Historical Categorization of Japanese Blades in Martial Context,” Bulletin of Asian Arms Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 123–138, 2005.

Leave a comment